Brief Overview

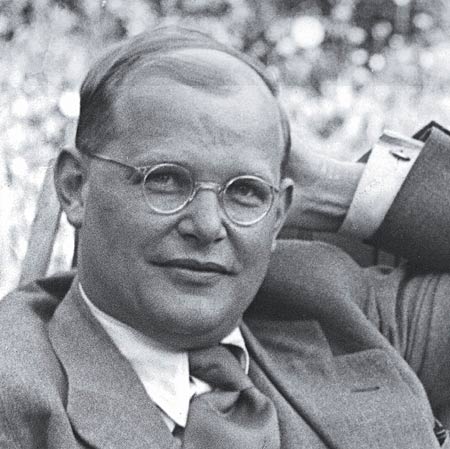

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) was a German pastor, theologian, ecumenist, and peace activist. He wrote profoundly about Christian faith, community, grace, and ethics, centered in one way or another on the question, who is Christ for us today? The atrocities of the Nazi Regime, which resulted in unspeakable human suffering, compelled him to participate in a conspiracy that tried unsuccessfully to assassinate Hitler and install a new government that would end the war and those atrocities. Imprisoned during the last two years of his life, Bonhoeffer was executed just weeks before the end of the war.

Introduction to Dietrich Bonhoeffer

[Edited] Excerpt from “Exploring the Life and Theology of Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” a Westar Institute Webinar (2/10/2021), by Lori Brandt Hale. Edited in consultation with Victoria Barnett (10/10/2023).

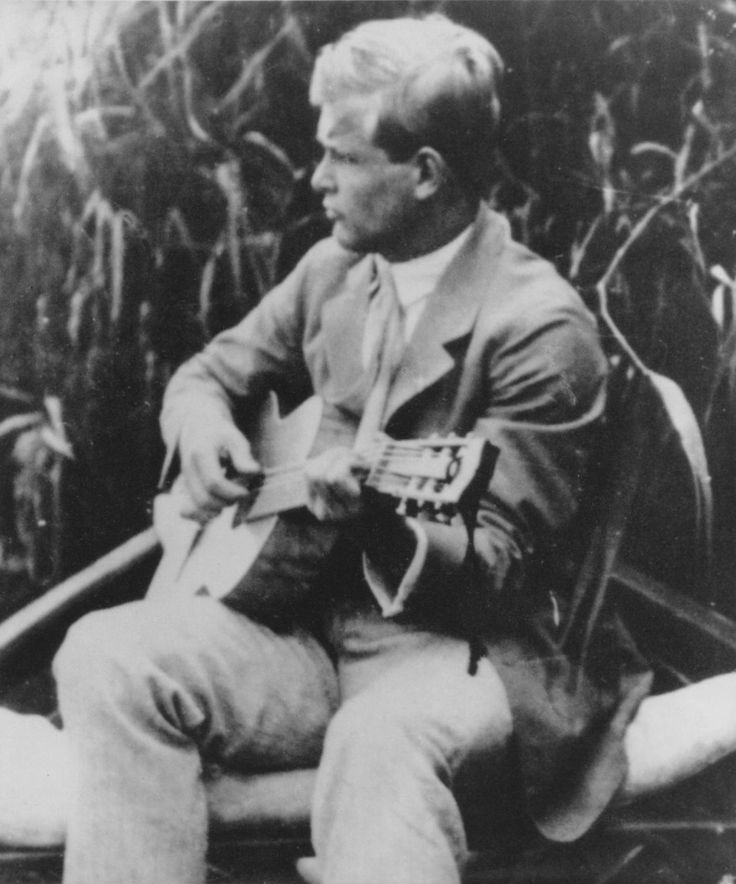

Dietrich Bonhoeffer – the well-known theologian, pastor, and Nazi resister – was born on February 4th, 1906, along with his twin sister, Sabine, into a large, tight-knit family that was highly educated, politically engaged, but only nominally religious. There were “churchmen” on Paula Bonhoeffer’s (Dietrich’s mother’s) side of the family, including a court chaplain (Dietrich’s grandfather) and a theologian (his great-grandfather), but no one expected Dietrich to study theology or pursue a career in the church. In fact, he was a prodigious pianist, playing chamber music by the age of eight, and there was some thought that he would become a professional musician. But, in 1918, when Dietrich and Sabine were twelve years old, their older brothers – Karl-Friedrich and Walter – left to fight for the monarchy in what would be the last year of the first world war. Karl-Friedrich returned, but Walter did not. He was wounded, and died, just a few weeks after his departure from home. His death took an emotional toll on the family and raised deep existential questions for the young Dietrich – about life, death, and the nature and impact of violent political realities (see DBWE 9:9). By age fourteen, Dietrich Bonhoeffer decided and announced that he would become a theologian and minister (Bethge 36). His mother was not surprised, but his brothers, Karl-Friedrich and Klaus, were openly scornful (Schlingensiepen 16). They found “religion a distraction from the urgent work of promoting equality and human rights” and “warned that becoming a theologian would amount to a retreat from reality” (Marsh 17).

Bonhoeffer’s theological path would not, in fact, lead him away from the world, but more deeply and profoundly into it. His execution at the hands of the Nazis, for his role in opposing them, bears this out. Famously, he wrote in his “Account at the Turn of the Year 1942-1943,” addressed to his co-conspirators, the “ultimately responsible question is not how I extricate myself heroically from a situation but [how] a coming generation is to go on living” (DBWE 8:42). A few pages later, in that same essay, Bonhoeffer reiterates his commitment to the world. “There are people who think [optimism] frivolous and Christians who think it impious to hope for a better future on earth and to prepare for it… they withdraw in resignation or pious flight from the world, from the responsibility for ongoing life, for building anew, for the coming generations. It may be that the day of judgment will dawn tomorrow; only then and no earlier will we readily lay down our work for a better future” (DBWE 8:51) From his earliest work on, Bonhoeffer’s theology and ethics are premised on what he will come to describe in his Ethics as the irreversible situation in which we always find ourselves, namely, “we are living” (DBWE 6:246). It is really no surprise, then, that these early commitments coupled with his historical context should lead him to explore ideas about this-worldly Christianity in his last years, while writing from prison.

There is an old adage among folks pursuing doctoral degrees that the best dissertation is a finished dissertation. But I contend that Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s dissertation stands as an exception to that rule. It is not possible to understand the whole of Bonhoeffer’s theology without a careful look at his dissertation, or said another way, Bonhoeffer’s key theological concepts – that he develops over the course of his life – can be found in the dissertation, Sanctorum Communion: A Theological Inquiry into the Sociology of the Church, written when he was 21 years old. The editor’s introduction to the critical English edition is helpful in laying out these ideas: he “articulates the concept of ‘person’ in ethical relation to the ‘other,’ Christian freedom as ‘being-free-for’ the other, the reciprocal relationship of person and community, vicarious representative action as both a Christological and an anthropological-ethical concept, the exercise by individual persons of responsibility for human communities, social relations as analogies of divine-human relations, and the encounter of transcendence in human sociality” (DBWE 1:1). In other words, Bonhoeffer determines that his basic existential, ontological, theological, and ethical questions have an integrated answer, that “the concepts of person, community, and God are inseparably interrelated” (DBWE 1:34). Accordingly, when one encounters an ‘other’ that ‘other’ places an ethical demand on me.

After finishing his dissertation in 1927, Bonhoeffer became the associate pastor of a German congregation in Barcelona. In the sermons and lectures he gave that year (it was just a one-year post), a tension in his theology became quite evident. On one hand, that ethical imperative to respond to the ‘other,’ derived from his theology (more specifically, from his Christology), served as a guide for starting to think about how to act with and for others. On the other hand, he was still quite sympathetic to German nationalism and had been shaped by a triumphalist theology. It wasn’t until he spent a year in New York at Union Theological Seminary (the 1930-31 academic year) that he would recognize the ways that suffering, the suffering of real human beings in the world, racialized human beings, would and could shape his theological understanding.

It would be very difficult to overstate the impact Bonhoeffer’s year at Union had on his life and thought. Despite the fact that Bonhoeffer was quite unimpressed, initially, with his course of study, his experiences (including travel), his observations, and his friendships were life-changing. From Professor Reinhold Niebuhr, to friends Paul and Marion Lehmann, Erwin Sutz, Jean Lassere, and Albert Franklin Fisher, Bonhoeffer was pressed to examine many of his own assumptions and began to see the events of the world from below, from the perspective of the marginalized and disenfranchised.

Lassere was a French pacifist who challenged Bonhoeffer’s reading of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount; he confronted Bonhoeffer with new ideas about the relationship between the Biblical text, God’s word, and living out that word as a citizen of the world, taking seriously Jesus’ peace commandment. By November of 1930, on Armistice Day, Bonhoeffer preached at a Methodist church in Yonkers, New York and began to articulate what would become his own ecumenical, peace ethic: “I stand before you,” he said, “not only as a Christian but also a German, who loves his home the best of all, who rejoices with his people and who suffers, when he sees his people suffering, who confesses gratefully, that he received from his people all that he has and is… [He went on] You have brothers and sisters in our people and in every people, do not forget that. Come what may, let us never more forget, that our Christian people is the people of God, that if we are in accord, no nationalism, no hate of races or classes can execute its designs, and then the world will have its peace for ever and ever” (DBWE 10:581, 584). Lassere reasserted this sentiment in a book published eight years after Bonhoeffer’s death when he wrote, “nothing in the Scriptures gives the Christian authority to tear apart the body of Christ for the State or anything else… one cannot be Christian and nationalist” (Bethge 154).

Albert Franklin Fisher was an African American student who opened the doors to Harlem and the Abyssinian Baptist Church for Bonhoeffer, and opened his eyes to the grave racial inequities and indignities in the United States. Bonhoeffer taught Sunday School at Abyssinian, became involved in various church clubs and studies, collected gramophone records of spirituals, and visited with church members in their homes. He also read the novels and poetry of many Harlem Renaissance writers – WEB DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Alaine Locke, Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes – and he concluded that the mood in this literature indicated that “the race question is arriving at a turning point. The attempt to overcome the conflict religiously or ethically will turn in a violent political objection” (DBWE 10:422). [There is a footnote in the text that says by “objection” he probably meant “resistance.”]

Reggie Williams explores the impact of this year in New York on Dietrich’s thinking in his 2014 book titled Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance. Williams writes, “Most white liberals failed to see white supremacy as a matter for Christian attention, and as a consequence they ignored the constant dangers of daily life in America for black people. But avoiding racism was not a choice for African American Christians; it was a matter of life and death in a society organized by race and enforced by violence. Consequently, Bonhoeffer’s friendship with Albert Fisher introduced him to Christian worship with an inherently different view of society. With Fisher, Bonhoeffer encountered Christians aware of human suffering and accustomed to living with the threat of death in a society organized by a violent white supremacy” (Williams 21-22).

So, Lassere, Fisher, Niebuhr and the others were instrumental in Bonhoeffer’s move toward ecumenism and internationalism, a move which came to fruition when he returned to Germany and took on roles as a youth secretary in both the World Alliance for Promoting International Friendship through the Churches and in the Ecumenical Council for Practical Christianity. In the two years after he returned from Union, Bonhoeffer engaged in this ecumenical work (which required travel throughout Europe) as well as lectured as a member of the theological faculty of Berlin University and served as a student chaplain, delivering sermons and teaching confirmation class in a working-class neighborhood of Berlin, a community riddled with unemployment and poverty. He found himself “moved by these people on the margins” (Marsh 148). His work in the church and the community – both in New York and Berlin – influenced his academic inquiry and teaching. Even in class his questions were less exercises in academic abstraction and conjecture, and more existential and urgent questions about life and faith, eventually leading him to the question: who is Jesus Christ for us today?

The rise of the National Socialists in Germany had concerned the Bonhoeffer family since before Dietrich’s return from New York; the ascent of Adolf Hitler to power at the very end of January 1933 brought their fears to the fore. On February 1st, Bonhoeffer delivered a radio address warning his fellow Germans that to make an idol of the Führer (the leader) is to make him a misleader… [Moreover] the leader must radically reject the temptation to become an idol” which would be to mistake, or misappropriate, the penultimate for the ultimate. Those who make this misappropriation, who concede responsibility to a “Superman” will, in the end, be destroyed by him (see DBWE 12:281).

The early weeks of the Nazi government were turbulent. The political violence that had marked the early 1930s in Germany continued, but now Nazi storm troopers and paramilitary groups had free rein. The regime immediately targeted real and potential enemies, particularly Communists, journalists, and others. The first concentration camp, Dachau, was opened in March 1933 and on March 23rd the German Parliament passed the Enabling Act, which consolidated all power in Hitler. Germany was now a dictatorship. On the 1st of April, a nationwide boycott of Jewish business drew international attention. It was followed by a new racial law, the April 7th “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service,” designed to remove all Jews and persons of Jewish descent from the civil service. The state left implementation of the April 7th law up to the respective institutions, including the Protestant Church.

These measures found approval within a significant sector of the German Protestant Church: the “German Christian Faith Movement.” Founded in 1932, the German Christians were an antisemitic, nationalist group that embraced Nazi ideology, notions of a racially pure church, and the idea of aligning the church with the Nazi state. Its leader was a former military chaplain and longtime Nazi Party member, Ludwig Mueller. This made the movement an ideal ally for Hitler’s purposes of consolidating state power and Hitler initially championed the notion of a “Reichskirche,” – a single, national, state church that would unify twenty-eight independent, Protestant Landeskirche (regional churches).

The attempt at a Reichskirche was ultimately abandoned, largely because of the bitter internal battles among the Protestant churches that ensued, about the question of an “Aryan paragraph” that would bar Christians of Jewish descent from the ministry. (In 1933, there were about 90 Protestant clergy of Jewish descent out of 18,000). The German Christians embraced the idea and, following the April 7th state law, immediately pushed for a church “Aryan paragraph.” Many others, including those who would eventually form the Confessing Church, were opposed to such an idea. The ensuing conflict, known as the Church Struggle (Kirchenkampf), was nothing less than the struggle – as Ludwig Mueller himself put it – “for the soul of the people” (Barnett 4).

In the early days of 1933, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was one of the first to recognize “Hitler’s policies against the Jews as a problem for the church… and eminently a political one” (Schlingensiepen 125). He began writing his essay, “The Church and the Jewish Question,” even before the April 7th civil service law was issued (Schlingensiepen 125). In it he claimed that the church has the right and responsibility to question the legitimacy of the state, to aid victims of the state even if they are not Christian, and (famously) to jam the spokes of the wheel of the state, or “seize the wheel” of the state, if the state’s actions lead to the “lack of rights and disorder” (DBWE 12:365; see DBWE 12:364, n.9).

Bonhoeffer, then, was already fighting several battles within the church that had broader implications. In September of 1933, Bonhoeffer joined Martin Niemöller and others to form the Pastors’ Emergency League (PEL) to help clergy who had already been dismissed. But, while the “founding statement of the PEL pledged to protest all infringements on confessional freedom by the state and explicitly opposed the ‘Aryan Paragraph,’” [in that opposition]… the PEL distinguished between Jews and Jewish Christians” (Barnett 35, my emphasis). Problematically, “its concern was for the latter” (Barnett 35). For Bonhoeffer, the church struggle that did not take up Nazi racial policy was a misdirected fight. “The struggle of the Confessing Church against the German Christians was from the beginning a struggle against the wrong opponent” (Schlingensiepen 142). In both frustration and humility, Bonhoeffer left for London in October of 1933 to lead two German-speaking churches to, in his words, “go into the wilderness for a spell, and simply work as a pastor, as unobtrusively as possible” (DBWE 13:22-23).

Despite his hope to work unobtrusively, Bonhoeffer continued to pay attention to developments in Germany and reject the idea being purported by the leadership of the German Christians in Berlin that the work of the Third Reich was some kind of fulfillment of scripture, an unholy kairos, if you will. He rejected the words of German Christian leader Reinhold Krause, who said, “When we draw from the gospel that which speaks to our German hearts, then the essentials of the teaching of Jesus emerge clearly and revealingly, coinciding completely with the demands of National Socialism, and we can be proud of that” (Tietz 47). Rather, Bonhoeffer preached that Christians “should read the Bible not only ‘for’ ourselves… but also ‘against’ ourselves” to know and love the world in which we actually live, even one filled with struggle, poverty, and uncertainty (Best xxiii-xxiv). He remained active in the ecumenical movement, discussing developments in Germany with Bishop George Bell and other leaders, and he reunited with his friend, Jean Lassere, at a conference in Fanø, Denmark, in the summer of 1934, where Bonhoeffer insisted that the conference pass a resolution, proclaiming “we are immediately faced with the decision: National Socialist or Christian” (DBWE 13:192). It was here that he also issued a clarion call to peace, noting that peace is not reached by a path of security, but only with risk. “The hour is late,” he said. “The world is choked with weapons, and dreadful is the distrust which looks out of all men’s eyes. The trumpets of war may blow tomorrow. For what are we waiting?” (DBWE 13:309).

The passage on the flyer advertising today’s event [the Westar Institute Webinar] comes from a sermon Bonhoeffer gave in London, on an unknown date in 1934: “Christianity stands or falls with its revolutionary protest against violence, arbitrariness, and pride of power, and with its plea for the weak” (DBWE 13:402). It is not a very well-known Bonhoeffer quote, though the sermon – based on 2 Corinthians 12:9 (“my strength is made perfect in weakness”) – made it into Isabel Best’s 2012 volume of The Collected Sermons of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, which only includes 31 texts. Best offers some context; she notes that some of Bonhoeffer’s work with the Pastors’ Emergency League had taken place at Bethel, a care facility in Bielefeld, Germany for persons with mental and physical disabilities. He had been struck by their vulnerability – especially in the Nazi context – and what he imagined to be their “better insight into certain realities of human existence” (Best 167). In July of 1934, he arranged for his congregations in London to send donations to Bethel. It strikes me that his concerns for these people – lingering nearly a year after he met them – are resonant with his early understanding that the “Other” places an ethical demand on me, calling me to respond; moreover, his concerns for these folks, and others on the margins, continue to shape his theological thinking until his last days, when he writes from Tegel prison that “human religiosity directs people in need to the power of God in the world, [toward the false concept of] God as deus ex machina. The Bible directs people toward the powerlessness and the suffering of God; only the suffering God can help” (DBWE 8:479). This shift in perspective, he goes on to say, will be the starting point for his “worldly interpretation” of (Christian) faith (DBWE 8:480).

In the spring of 1935, Bonhoeffer accepted an invitation to direct a preachers’ seminary of the Confessing Church, first at Zingsthoff, then at Finkenwalde. His acceptance meant abandoning a planned trip to India, to study non-violent resistance with Gandhi. At Finkenwalde, Bonhoeffer tightly structured the days of the seminarians: time alone, time together, time for study, time for work, time for prayer, time for play. He was accused of legalism, of fostering a monastic retreat from the world, when – in fact – his intention was quite the opposite. His goal was to prepare the students for the difficult reality of life in parish ministry, in opposition to the Nazi regime. While there, Bonhoeffer wrote Discipleship, an important and popular text that often gets misread as a guide to Christian spirituality divorced from the world. Even Bonhoeffer, later – in his Letters and Papers from Prison – warns against reading the text in this way. Rather, Discipleship – with attention to the Lutheran concept of grace, developed as costly grace, and a considered reading of the Sermon on the Mount – is an astute, politically informed, call to live vicariously and suffer vicariously on behalf of others, in commitment and obedience to Christ. (To be blatantly obvious, Bonhoeffer emphasizes obedience to Christ over against obedience to Hitler.)

The seminary was considered “illegal” under church law–the official church consistory in Berlin did not recognize the theological training of candidates who attended any of the five Confessing seminaries. At the end of August 1937,the Confessing seminaries were declared illegal in a decree from Heinrich Himmler; Finkenwalde was closed by the Gestapo on September 28th, 1937. Bonhoeffer’s resistance to the Third Reich to this point meant that he had limited options for work, including publishing and speaking. His friends abroad were worried for his safety in the increasingly hostile Nazi environment and, so, in June of 1939 he returned to the United States with all in order to stay through the pending catastrophe. But Bonhoeffer never felt settled about his decision to go, and returned to Germany by the end of July. “Christians in Germany will face a terrible alternative of either willing the defeat of their nation in order that Christian civilization may survive, or willing the victory of their nation and thereby destroying our civilization,” he wrote to Niebuhr. “I know which of these alternatives I must choose, but I cannot make that choice in security” (DBWE 15:210).

“I cannot make that choice in security.” Bonhoeffer knew the weight of this statement when he made it because his brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi, a member of the Abwehr, the German Military Intelligence, had informed him of the coup being planned in that office, involving Admiral Wilhelm Canaris and General Hans Oster. Von Dohnanyi was able to secure Bonhoeffer an appointment that set Dietrich up as a double-agent, ostensibly using his ecumenical contacts throughout Europe to gather information for the Nazis when actually he was passing information about the resistance in the other direction. In this context, he began work on his Ethics, which he envisioned as his magnum opus. In it, he rejects the idea that ethics can be universally valid or derived from general principles. Rather, he advances a Christological understanding of responsibility that is tied to concrete reality and reiterates his idea that one is called to respond to an ‘other’ in need:

“Christ was not essentially a teacher, a lawgiver, but a human being, a real human being like us. Accordingly, Christ does not want us to be first of all pupils, representatives and advocates of a particular doctrine, but human beings, real human beings before God. Christ did not, like an ethicist, love a theory about the good; he loved real people. Christ was not interested like a philosopher, in what is ‘generally valid,’ but in that which serves real concrete human beings. Christ was not concerned with whether “the maxim of an action” could become “a principle of universal law,” but whether my action now helps my neighbor to be a human being before God. God did not become an idea, a principle, a program, a universally valid belief, or a law. God became human” (DBWE 6:98-99).

In letters to his best friend and eventual biographer, Eberhard Bethge, as well as Paul Lehmann, Bonhoeffer wrote that he found his work on Ethics “dangerous” and “stimulating.” “Sometimes I think after this time,” he said, “that Christianity will only live in a few people who have nothing to say” (DBWE 16:168).

On April 5th, 1943, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was arrested on tenuous charges – related to his role in the Abwehr, but unrelated to the plot to kill Hitler. He was sent to Tegel prison in Berlin. While many readers of Bonhoeffer return again and again to Discipleship or Life Together (his brief account of life at Finkenwalde), I find myself drawn to the Letters and Papers from Prison. In fact, before the new critical editions of Bonhoeffer’s works were published by Fortress Press, my paperback copy of Letters was bound together with rubber bands and paper clips. (Two of my students “borrowed” my book, a dozen years ago, and had it bound for me.) I am drawn to the questions and conclusions Bonhoeffer reaches in his prison reflections, even though they are incomplete – questions about the possibility of a religionless interpretation of Christianity that means one only “learns to have faith by living in the full this-worldliness of life… living fully in the midst of life’s tasks, questions, successes and failures, experiences, and perplexities – then one takes seriously no longer one’s own sufferings but rather the suffering of God in the world… this is faith; this is metanoia. And this is how one becomes a human being, a Christian” (DBWE 8:486).

On July 20th, 1944, the final attempt on Hitler’s life failed. Two months later the Gestapo discovered the files (a secret archive) of the Resistance. Bonhoeffer was implicated in the planned coup; he knew he would never be released. In his theological and ethical work, he never offered a justification for tyrannicide. He wrote of freedom and responsibility, and taking on guilt. In that essay written to his co-conspirators, after ten years of Hitler’s rule, he named the “great masquerade of evil” that “has thrown all ethical concepts into confusion” (DBWE 8:38). He wondered “who stands firm?” asserting that “civil courage can grow only from the free responsibility of the free man… It is founded on a God who calls for the free venture of faith to responsible action and who promises forgiveness and consolation to the one who on account of such action becomes a sinner” (DBWE 8:40, 41). Bonhoeffer closes that essay with what I might call the hermeneutical key, the interpretive lens, for the whole of his work and life. It is a section called “the view from below.” “It remains an experience of incomparable value that we have for once learned to see the great events of world history from below, from the perspective of the outcasts, the suspects, the maltreated, the powerless, the oppressed and reviled, in short from the perspective of the suffering” (DBWE 8:52).

On April 9th, 1945, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was marched, naked, to the gallows at Flössenburg Concentration Camp and hanged. He was 39 years old. The camp was liberated a few weeks later. His family and friends, including his fiancé, Maria von Wedemeyer, did not learn of his death until the end of June. His brother, Klaus, and brothers-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi and Rudiger Schleicher, were all executed the same week in April as Dietrich.

Selected Works

The Dietrich Bonhoeffer Works in English (DBWE) published by Fortress Press (Minneapolis, MN) with various editors and translators, (1996-2014). (This essay cites volumes 1, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16.)

DBWE 1: Sanctorum Communio

DBWE 2: Act and Being

DBWE 3: Creation and Fall

DBWE 4: Discipleship

DBWE 5: Life Together and Prayerbook of the Bible

DBWE 6: Ethics

DBWE 7: Fiction from Tegel Prison

DBWE 8: Letters and Papers from Prison

DBWE 9: The Young Bonhoeffer, 1918-1927

DBWE 10: Barcelona, Berlin, New York, 1928-1931

DBWE 11: Ecumenical, Academic, and Pastoral Work, 1931-1932

DBWE 10: Barcelona, Berlin, New York, 1928-1931

DBWE 11: Ecumenical, Academic, and Pastoral Work, 1931-1932

DBWE 12: Berlin, 1932-1933

DBWE 13: London, 1933-1935

DBWE 14: Theological Education at Finkenwalde, 1935-1937

DBWE 15: Theological Education Underground, 1937-1940

DBWE 16: Conspiracy and Imprisonment, 1940-1945

DBWE 17: Index and Supplementary Materials

Barnett, Victoria. For the Soul of the People: Protestant Protest against Hitler. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Bergen, Doris. War and Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust. Third Ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Bethge, Eberhard. Dietrich Bonhoeffer: A Biography, translated by Victoria J. Barnett. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2000.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. The Collected Sermons of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, translated and edited by Isabel Best. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012.

Marsh, Charles. Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2014.

Schlingensiepen, Ferdinand. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, 1906-1945: Martyr, Thinker, Man of Resistance. New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2010.

Tietz, Christiane. Theologian of Resistance: The Life and Thoughts of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, translated by Victoria J. Barnett. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2016.

Williams, Reggie L. Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2014.

You must be logged in to post a comment.